Matthys Schouten, 2, and the twins Julia and Eliza Weix, 23 months, have the same sperm donor father.

The New York Times

By AMY HARMON

Published: November 20, 2005Like most anonymous sperm donors, Donor 150 of the California Cryobank will probably never meet any of the offspring he fathered through sperm bank donations. There are at least four, according to the bank's records, and perhaps many more, since the dozens of women who have bought Donor 150's sperm are not required to report when they have a baby.

Justin Senk, 15, right, was the most recent half-sibling to surface in a group that now numbers five.

But two of his genetic daughters, born to different mothers and living in different states, have been e-mailing and talking on the phone regularly since learning of each other's existence last summer. They plan to meet over Thanksgiving.

The girls, Danielle Pagano, 16, and JoEllen Marsh, 15, connected through the Donor Sibling Registry, a Web site that is helping to open a new chapter in the oldest form of assisted reproductive technology. The three-year-old site allows parents and offspring to enter their contact information and search for others by sperm bank and donor number.

"The first time we were on the phone, it was awkward," Danielle said. "I was like, 'We'll get over it,' and she said, 'Yeah, we're sisters.' It was so weird to hear her say that. It was cool."

For children who often feel severed from half of their biological identity, finding a sibling - or in some cases, a dozen - can feel like coming home. It can also make them even more curious about the anonymous father whose genes they carry. The registry especially welcomes donors who want to shed their anonymity, but the vast majority of the site's 1,001 matches are between half-siblings.

The popularity of the Donor Sibling Registry, many of its registrants say, speaks to the sustained power of biological ties at a time when it is becoming almost routine for women to bear children who do not share a partner's DNA, or even their own.

"I hate when people that use D.I. say that biology doesn't matter (cough, my mom, cough)," Danielle wrote in an e-mail message, using the shorthand for donor insemination. "Because if it really didn't matter to them, then why would they use D.I. at all? They could just adopt or something and help out kids in need."

The half-sibling hunt is driven in part by the growing number of donor-conceived children who know the truth about their origins. As more single women and lesbian couples use sperm donors to conceive, children's questions about their fathers' whereabouts often prompt an explanation at an early age, even if all the information about the father that is known is his code number used by the bank for identification purposes and the fragments of personal information provided in his donor profile.

Donor-conceived siblings, who sometimes describe themselves as "lopsided" or "half-adopted," can provide clues to make each other feel more whole, even if only in the form of physical details.

Liz Herzog, 12, and Callie Frasier-Walker, 10, for instance, carry the same dimple near their right eye.

"She looks up to me," said Liz, of Chicago, who was an only child before learning of Callie and six other half-siblings but seemed to have had no trouble stepping into her older-sister role. Finding her brothers and sisters, Liz said, "was the best thing in the world," even if Callie does copy her sometimes, like when Liz got her hair dyed red and Callie did the same. "I wanted blue," Callie said. "But they didn't have blue."

The two girls, who send instant messages to each other frequently, will be spending Thanksgiving with their mothers at Callie's house in Chester Springs, Pa. They had a mini-family reunion with some of their other siblings last April, although as Liz's mother, Diana Herzog, notes, "It wasn't really a reunion because no one had ever met before."

Many mothers seek out each other on the registry, eager to create a patchwork family for themselves and their children. One group of seven say they too feel bonded by the half-blood relations of their children, and perhaps by the vaguely biological urge that led them all to choose Fairfax Cryobank's Donor 401.

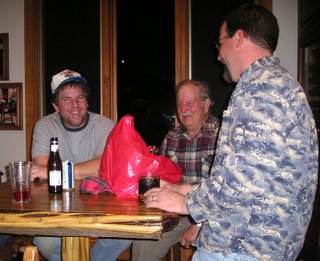

Carla Schouten sent a leftover vial of sperm to another mother who wanted to have a second child and found there was no 401 sperm left to buy. (Banks typically pay men $50 to $100 per sample, and customers pay about $150 to $600 per vial, plus shipping.) In July, Ms. Schouten and her 2-year-old son, Matthys, went camping in Northern California with Louisa Weix, and her Donor 401 twins, Eliza and Julia, who turn 2 next week.

While many donor-conceived children prefer to call their genetic father "donor," to differentiate the biological function of fatherhood from the social one, they often feel no need to distance themselves, linguistically or emotionally, from their siblings.

Several who have met describe a sense of familiarity that seems largely irrational, given the absence of a father, unrelated mothers and often divergent interests.

"All I can say is, they feel like siblings," said Barry Stevens, 53, a filmmaker who has discovered several half-siblings through research and DNA testing since the release of his 2001 documentary, "Offspring," depicting his search for his donor.

If yearning for a sibling is in part a desire to feel less alone, some donor-conceived children may ultimately find themselves yearning for a bit more solitude.

Deb Bash, the mother of a 7-year-old, exchanges e-mail messages often with eight other mothers who have a total of 12 children from the same donor, and she has created a baby book for her son with all their pictures. The siblings, Ms. Bash said, have given her son a way to feel connected to the otherwise abstract concept of a genetic father.

"It's not a phantom person out there anymore," Ms. Bash said.

The children already have some uncanny resemblances, she said. "That nurture vs. nature," Ms. Bash added. "Wow, there's just something to that nature."

For Danielle, of Seaford, N.Y., contact with her half-sibling JoEllen has helped salve her anger at what she describes as "having been lied to all my life," until three years ago when her parents told her the truth about her conception. It has also eased her frustration of knowing only the scant information about her biological father contained in the sperm bank profile - he is 6 feet tall, 163 pounds with blond hair and blue eyes. He was married, at least at the time of his donation, and has two children with his wife. He likes yoga, animals and acting.

For JoEllen, whose two mothers told her early on about her biological background, it helps just to know that Danielle, too, checks male strangers against the list of Donor 150's physical traits that she has committed to memory.

"It'll always run through my mind whether he meets the criteria to be my dad or not," said JoEllen, of Russell, Pa. "She said the same thing happens with her."

The girls are considering a trip to Wilmington, Del., which Donor 150 listed as his birthplace.

Even as the Internet makes it easier for donor-conceived children to find one another, some are calling for an end to the system of anonymity under which they were born. Sperm banks, they say, should be required to accept only donors who agree that their children can contact them when they turn 18, as is now mandated in some European countries.

That is partly for reasons of accountability. Sperm bank officials estimate the number of children born to donors at about 30,000 a year, but because the industry is largely unregulated, no one really knows. And as half-siblings find one another, it is becoming clear that the banks do not know how many children are born to each donor, and where they are.

Popular donors may have several dozen children, or more, and critics say there is a risk of unwitting incest between half-siblings. Moreover, they argue, no one should be able to decide for children before they are born that they can never learn their father's identity. Typically, women can learn about a donor's medical history, ethnic background, education, hobbies and a wide range of physical characteristics.

More recently sperm banks have begun to charge more for the sperm from donors who agree to be contacted by their offspring when they turn 18. But they say far fewer men would choose to donate if they were required to release their identity.

Like Wendy Kramer and her donor-conceived son, Ryan, 15, who founded www.donorsiblingregistry.com, many of the site's 5,000 registrants hope that the donor himself will get in touch. But others are happy to settle for contacting their half-siblings, who actually want to be found. As they do, they are building a new definition of family that both rests on biology and transcends it.

"It's so weird to know that you're going to meet someone that you're going to know for the rest of your life," Justin Senk, 15, told his half-sister Rebecca Baldwin, 17, when they spoke on the phone last summer before meeting for the first time.

Justin, 15, of Denver, was the most recent half-sibling to surface in a group that now numbers five. After his newfound family attended his recent choir concert, Justin's mother, Susy Senk, overheard him introducing them to his friends with a self-styled sing-song, " 'This is my sister from another mother, and this is my brother from another mother, this is my other sister from another mother' and so on."